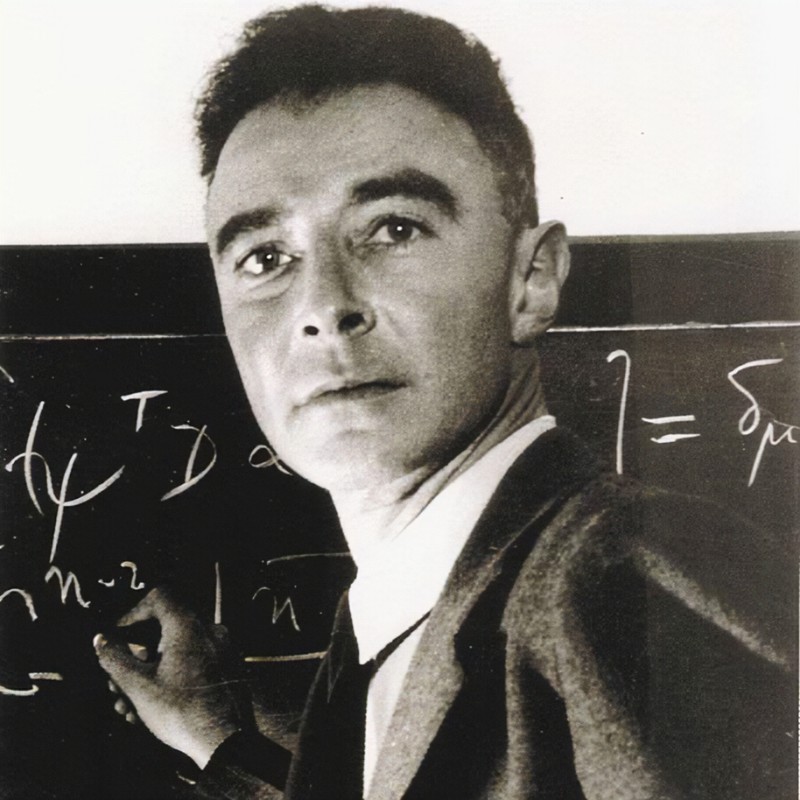

The Oscars are coming up this Sunday, and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is expected to make a big showing. The film has received thirteen Oscar nominations, including for the categories of best picture, best lead actor (Cillian Murphy), best director (Christopher Nolan), best supporting actor (Robert Downey Jr.), and best supporting actress (Emily Blunt).

With Oppenheimer at its most talked about point since its release in July, it only seems right to look back at the movie’s roots and give credit to those who laid the groundwork.

The Oppenheimer screenplay was adapted from American Prometheus, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s masterpiece chronicling the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, from birth, to bomb, to death, and everything in between. The book, coming in at almost six hundred pages—well over seven hundred when counting its numerous pages of extensive research and bibliographies—is the product of twenty-five years of hard labor on the part of Bird and Sherwin.

Sherwin signed a contract to start the book in 1980 and expected to finish writing within five years. When he realized the immensity of the task in front of him, he soon recruited his friend, Kai Bird, for assistance. After almost three decades of researching, writing, and refining, Bird and Sherwin finally published their history of Oppenheimer in 2005.

To say the book became a success would be an understatement. Bird and Sherwin went to bat with one of history’s grandest larger-than-life figures, a daunting task for any biographer. And they hit it out of the park.

Since its publication, American Prometheus has won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, as well as the Best Book of the Year awards for the New York Times, Washington Post, and the Chicago Tribune. Christopher Nolan, when discussing his decision to adapt American Prometheus into a screenplay, called the biography “A riveting account of one of history’s most essential and paradoxical figures.”

American Prometheus is the quintessential biography. To any aspiring biographers out there nervous about writing your first book, look no further than the work of Bird and Sherwin for guidance. The sheer volume of historical research put into the project shines through, drawing on sources from the Library of Congress, FBI dossiers, and Oppenheimer’s personal writings to build one of the most comprehensive profiles of Oppenheimer available.

Even with its massive quantity of research, American Prometheus does not read like a history textbook, or like any of the other dense, unexciting biographies of Oppenheimer. The book manages to keep a remarkable pace across its several hundred pages. There is never a difficult moment, nor an overwhelmingly tedious stretch that must be fought through to reach a more exciting section. This is not to say the book is an easy read—not in its complex content, and certainly not in its font size, which borders on minuscule—but it is a fulfilling one.

What makes American Prometheus so successful is its ability to introduce readers not just to Oppenheimer the historical figure, but Oppenheimer the man. Bird and Sherwin masterfully examine every facet of Oppenheimer’s complex and often contradictory personality, reinforcing the notion that even the man who brought the fire of the gods down to earth is human like anyone else. Soon after reading, readers will be endearingly calling the physicist “Oppie,” just as Bird and Sherwin, along with Oppenheimer’s colleagues, often did.

The conveyance of Oppenheimer’s humanity, as displayed throughout American Prometheus, is one of Nolan’s film’s defining features, and is what sets the film apart from previous cinematic depictions of Oppenheimer, allowing the film to succeed in bringing the most intimate profile of to one of history’s most famed faces to life on the big screen.