New York City’s New Reading Program Has No Place on the Classroom Bookshelf

On Thursday May 11, New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced plans for the mandated implementation of a phonics-based reading curriculum known as “New York Reads,” effective by next school year.

New York City is one of several locations throughout the United States that are overhauling their traditional reading curricula in favor of one based on an educational theory known as the science of reading.

Where, traditionally, many educators have used the popular approach known as “balanced literacy” to teach reading, the science of reading is a way of going back to the basics. Experts like Lucy Calkins criticize balanced literacy for its emphasis on nurturing a love for books – a focus that those like Calkins say detracts from teaching core reading skills – and its use of controversial strategies like read-alouds, independent reading, and small group conversation.

The United States is no stranger to attempts to reform reading programs. The debate over the science of reading is just the latest point of contention on the battleground of reading curriculum, dubbed the reading wars, that can be traced back over a hundred years. But in a different sense, it also marks a significant change in educational priorities, one that, in its aim to encourage modern science, forgets the true value of a reading education.

There is certainly reason for change in the United States’ reading curricula. According to the PEW Research Center, the 2015 scores from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), one of the largest cross-national assessments, placed the US at 24th out of 78 countries in reading. For a member of the organization that sponsors the PISA initiative and the most populated country to speak English as a primary language, the score is embarrassingly unremarkable.

The goal of programs founded on the science of reading theory is to improve American literacy, pulling us out of the depths of global mediocrity, and they have certainly had their success stories.

According to a New York Times article, 60% of third graders at Panther Valley Elementary, a rural, low-income school in Eastern Pennsylvania are now proficient in decoding words, a whopping 30% increase from the beginning of the school year. Mississippi fourth-grade scores have improved a full ten points since beginning its implementation of the science of reading in 2013.

But despite its name, the science of reading has failed to scrounge up scientific evidence to indicate any true pattern of improvement or prove its long-term effectiveness. At a time where STEM fields dominate the current job industry and likely the future one as well, the orderly approaches rooted in scripted lesson plans and structured administrations may not be what the world of reading needs.

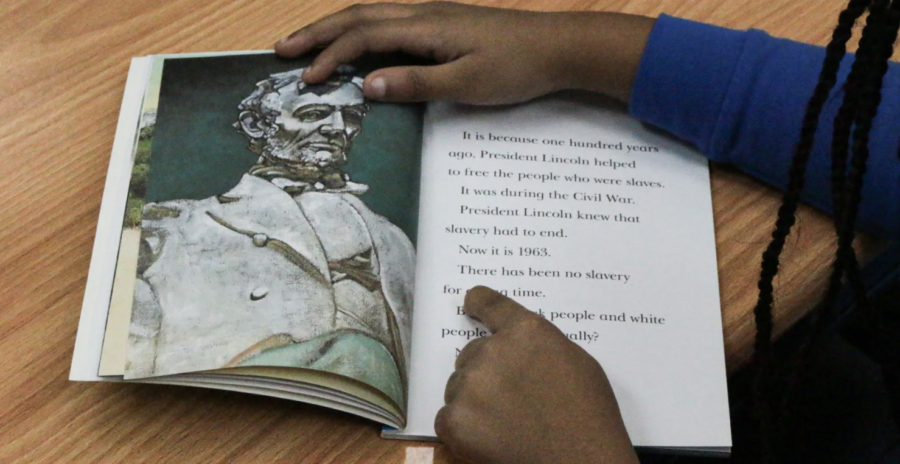

Instead, reading should be a time for children to not only learn the fundamentals of reading comprehension but enjoy reading and build an understanding of context clues and interactive reading. Indeed, being a reader goes beyond basic reading ability.

As an article by Cambridge University indicates, authentic readership requires engaged interaction with texts, thought and reflection, curiosity and interpretation – activities that are stifled when students become so far removed from the reading that they can no longer see its purpose beyond analyzing its fundamental form.

This isn’t the first time that a science-based reading program has gained popularity in the US. Eric Adams’ “New York Reads” campaign is hauntingly reminiscent of another controversial program known as “Reading First,” whose failures are echoed in the critiques against the newest revival of the science of reading.

Just like “Reading First,” the science of reading falls back on the idea of a one-size-fits-all program. Just like “Reading First,” it prescribes a systematic and structured format which, though practical, contradicts the very multi-faceted nature both of reading comprehension and the educational industry.

Teaching is dependent on the needs of the students, not just the educational policies of the school, which is why educators are equipped with multiple teaching strategies. To establish such a prescriptive program in a system with such variance is a gross mischaracterization of what a reading education is meant to achieve.

The paralleled stories of “New York Reads” and “Reading First” are reflections of a society that believes science has a place in everything. But rigidity has no role in a career and subject so rooted in subjectivity. By attempting to force students and teachers into a singular mold, administrations may be establishing a solid standard, but in the process, they have stripped reading of joy and humanity – the very things that give it value.